How were airports imagined at the beginning of the 20th century — and how do we see them today?

In what direction are the world’s largest airports developing, and which corporations are shaping them? How do global trends influence the evolution of airports in Russia? The aviation trends discussed here reveal how major air hubs are gradually transforming into a new kind of city — self-contained urban entities with their own economies, populations, and infrastructures.

From transport hubs to urban ecosystems

The current development of large airports — or, in urban terms, “aerotropolises” — increasingly resembles the materialization of the early 20th century’s visions of the city of the future. Modern airports seem to have absorbed every futuristic fantasy once imagined in architecture and urban planning — and in many cases, they have even surpassed those ideas. Today’s largest airports, handling anywhere between 30 and over 100 million passengers annually, function as independent cities. They have their own populations, territories, infrastructures, and management systems.

Airports such as Denver (USA), Schiphol (Netherlands), Frankfurt (Germany), and Doha (Qatar) are developing full-scale residential districts adjacent to their terminals. These provide housing for airport employees, representatives of international corporations, students of flight academies, and residents of nearby cities involved in global business.

In this sense, airports have become major city-forming enterprises that stimulate regional economies — creating jobs, attracting investment, and driving infrastructure development. Their growing commercialization has led to the expansion of services and amenities far beyond their physical boundaries, shaping vast zones of influence that integrate into the regional and global economy.

Infrastructure for life

Much like cities, airports now offer complete infrastructures for living: housing, offices, childcare facilities, schools, shopping malls, sports and wellness centers, public spaces, and even event programs that include international conferences, exhibitions, fairs, workshops, and excursions.

According to forecasts by international aviation organizations, the global annual passenger traffic will reach six billion by 2030. To meet this demand, airports are evolving into urban-scale systems, capable of supporting the growing mobility and service expectations of modern society.

It is estimated that more than one hundred potential aerotropolises are currently under development worldwide — in varying stages of implementation. New mega-hubs are already under construction in Qatar, the UAE, and Turkey, where the scale of planned passenger flows far exceeds the population of the countries themselves.

Airports of the future: from the 20th century to today

The aviation industry is little more than a century old. The first recorded flight took place in 1903 and lasted just twelve seconds. By 1914, the world’s first commercial airline — the Benoist Aircraft Company — began regular passenger services in the United States. Among the earliest still-operating airlines, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, founded in 1919, has retained its original name to this day.

The first civil airports with paved runways began handling scheduled flights after the First World War, mainly during the 1920s. Among the pioneers were airports in Atlantic City, Schiphol, Sydney, Minneapolis, Königsberg, Moscow, Kharkiv, and Hamburg.

Throughout the 20th century, aviation technology advanced rapidly — with innovations such as the autopilot, new engine types, and radar and communication systems. Aircraft evolved in efficiency and range, and airports followed suit, constantly adapting their infrastructure, logistics, and architecture.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the introduction of the world’s most popular aircraft models — the Boeing 737 and the Airbus A300 — both still in operation today. From the 1970s onward, market deregulation, first in the United States and later globally, made air travel more affordable and accessible, transforming aviation into a mass mode of transport.

Early visions of the future

In the early days of flight, there was no clear understanding of what an airport should be. However, airports were immediately associated with innovation — as symbols of modernity and progress, and as gateways to the “cities of the future.”

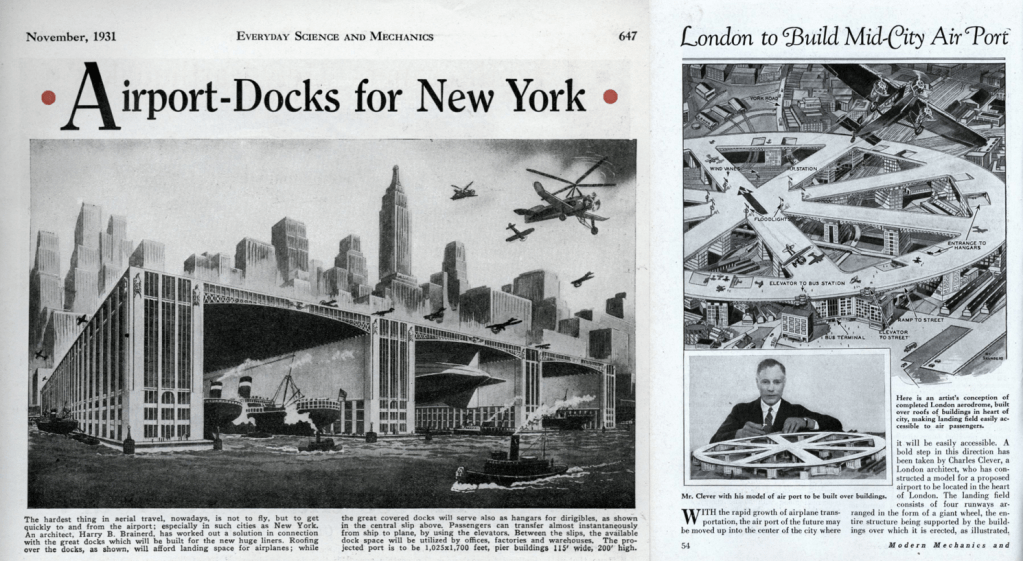

The ability to travel anywhere in the world — now taken for granted — once embodied a thrilling and revolutionary idea. Some of the earliest concepts of futuristic airports appeared in the 1920s, imagining facilities on skyscraper rooftops, circular airports, or multi-level transport hubs combining air terminals with maritime docks.

Fig. 1. Futuristic airport concepts of the 1930s. Source: Leigh Fisher.

In practice, few of these visionary concepts were ever realized. Airport architecture has always been constrained primarily by technical parameters, logistics, economics, and safety requirements. Even so, terminals have consistently reflected the technological ambitions of their time — giving architectural form to the public’s imagination of the future.

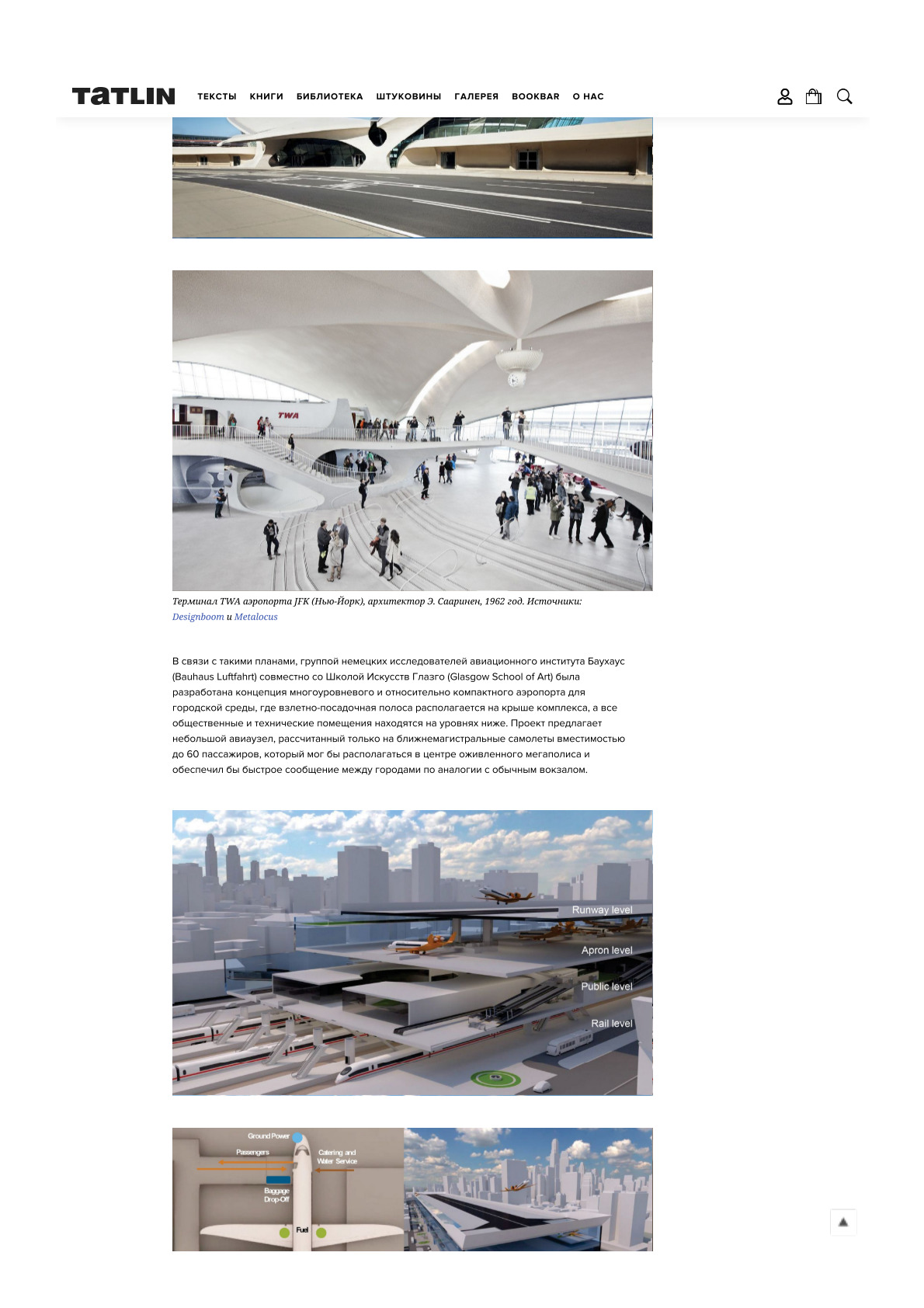

A vivid example is the TWA Flight Center at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, designed by Eero Saarinen and opened in 1962. Its sweeping, bird-like structure became a symbol of flight itself and still looks modern today. Now a protected heritage building, it has been carefully restored and transformed into a hotel, preserving Saarinen’s iconic vision for a new generation.

Fig. 2. TWA Terminal, JFK Airport (New York). Architect: Eero Saarinen, 1962. Sources: Designboom and Metalocus.

Despite the well-established system of modern airports, new futuristic concepts continue to appear from time to time — many of them reinterpreting or expanding on early 20th-century ideas. According to the European research initiative ACARE (Advisory Council for Aviation Research and Innovation in Europe), by 2050 the total “door-to-door” journey time for 90% of passengers in Europe should not exceed four hours. That goal sounds ambitious, considering how much time today’s travelers often spend simply reaching the airport and passing through security. Yet, on certain routes — for example, Munich to Berlin — this four-hour benchmark is already nearly achievable.

New urban airport concepts

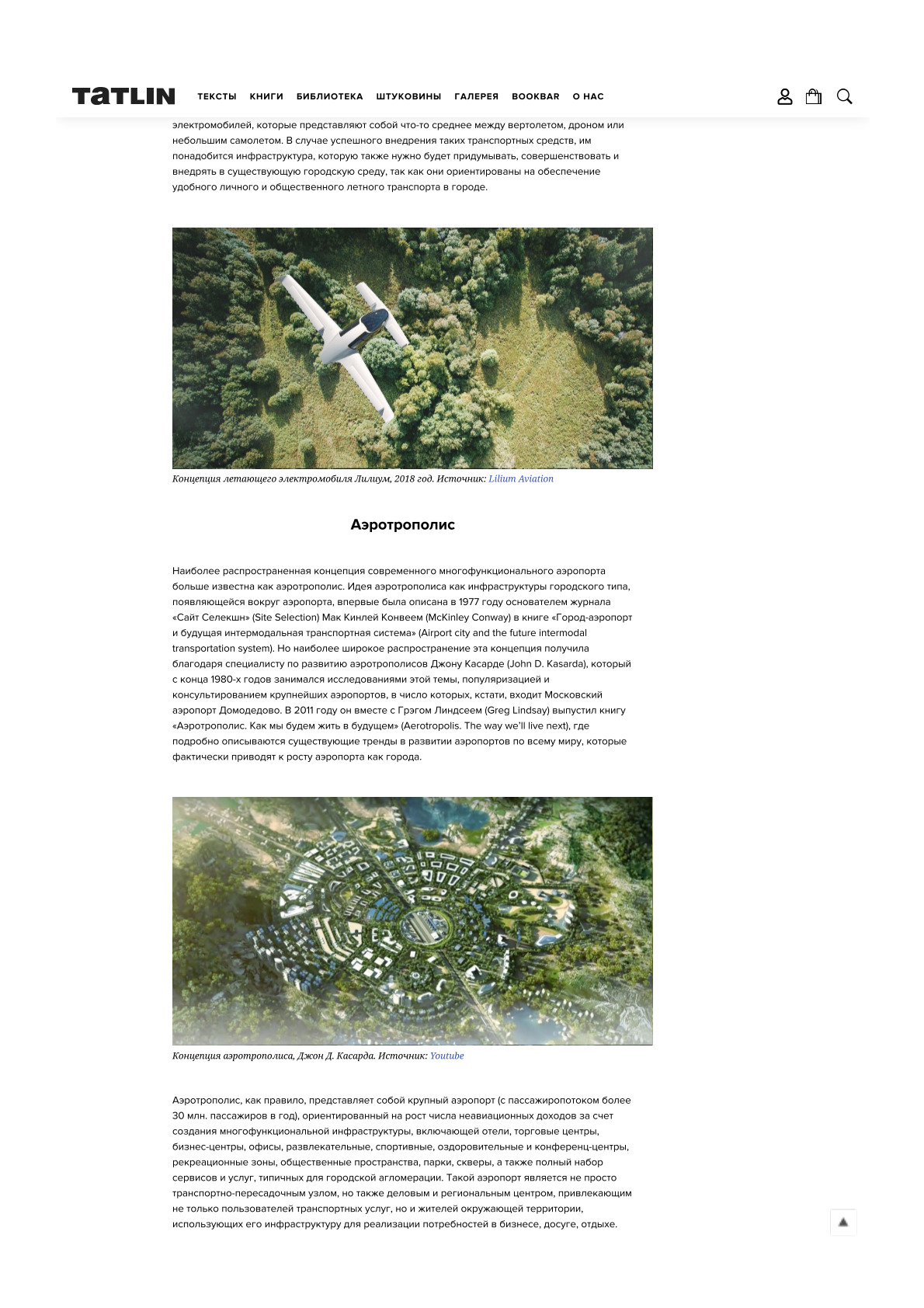

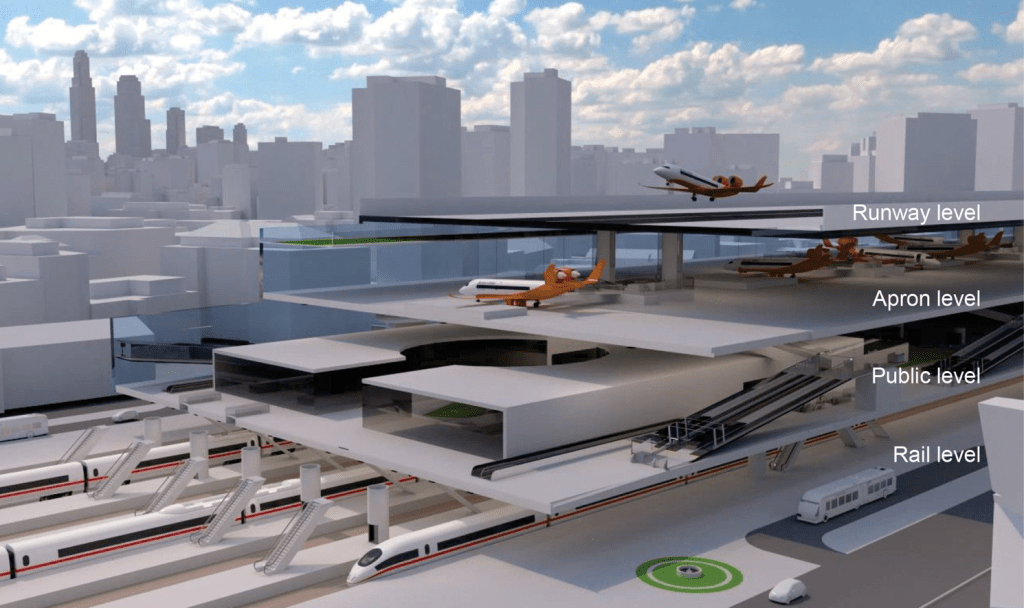

In line with such forecasts, researchers from Bauhaus Luftfahrt (the Bauhaus Aviation Institute) and the Glasgow School of Art developed a concept for a multi-level, compact airport designed specifically for the urban environment. In their proposal, the runway sits on the roof of the complex, while all public and technical spaces are arranged below. The design envisions a small hub for short-haul aircraft carrying up to 60 passengers, located directly within a dense metropolis — offering quick city-to-city connections similar to a conventional railway station.

Fig. 3. “Urban Airport” concept, Bauhaus Luftfahrt group, 2016. Source: DGLR.

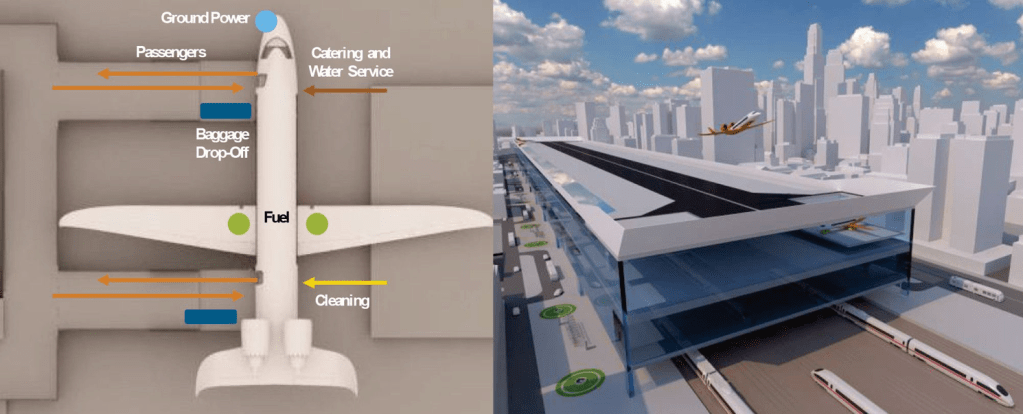

Another striking proposal came from the Netherlands Aerospace Centre, led by Henk Hesselink.

It explored the idea of a circular or “endless” runway. Theoretically, this geometry could provide the required take-off and landing distance while allowing aircraft to operate in any direction relative to the wind, simplifying maneuvers and improving braking efficiency through centrifugal force.

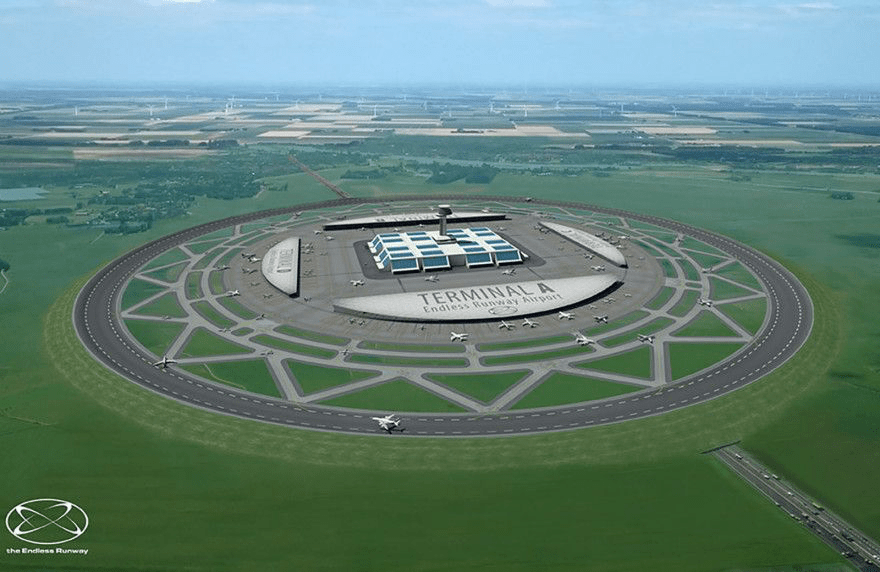

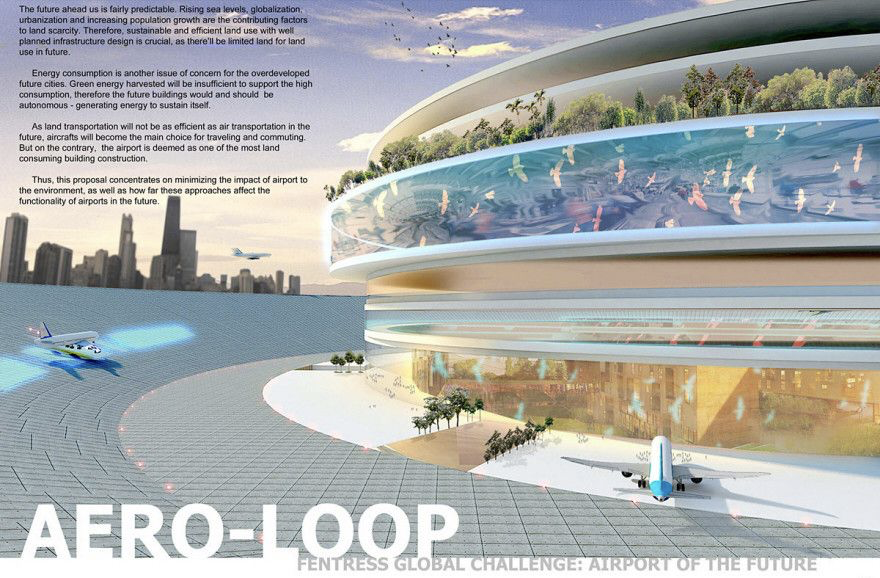

Interestingly, a few years earlier, a student from the University of Science, Malaysia, had presented a similar concept — a circular airport layout titled “Aero-Loop.”

Fig. 4. Circular runway airport concept, 2017. Source: NLR.

Fig. 5. Aero-Loop concept, Thor Yi Chun, 2011. Source: Bustler.

Airports of the future: competitions and vertical hubs

The Fentress Global Challenge — an annual international competition supported by Fentress Architects since 2011 — invites architects and students to envision the “Airport of the Future.” The format encourages bold experimentation, allowing participants to explore even the most speculative ideas that challenge conventional thinking about airport infrastructure.

Among the entries are designs for multi-level terminals, floating airports, eco-oriented hubs, and modular aviation complexes. Interestingly, unlike the early 20th-century visions that often reached skyward — placing airports on top of skyscrapers — many of today’s proposals suggest the opposite: burying infrastructure underground, concealing aprons, taxiways, and even runways beneath the surface.

In 2018, the Evolo Skyscraper Competition — known for selecting the world’s most innovative high-rise projects — awarded a special mention to a futuristic concept for Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). The project, titled “LAX 2.0: The Vertical Airport,” imagined a vertically organized transportation hub resembling the space stations of science fiction (top figure).

Such vertically integrated hubs are becoming an increasingly relevant theme in architectural competitions, reflecting expectations about the rise of personal aerial mobility — including flying taxis and drones. Around the world, numerous companies are now developing electric flying vehicles, hybrids of helicopters, drones, and small aircraft.

If successfully introduced, these new modes of transport will require a completely new type of infrastructure, one that must be designed, tested, and integrated into the existing urban fabric.

These vertiports and air-mobility nodes are set to become the next frontier in the evolution of the airport-city relationship.

Fig. 6. Lilium electric aircraft concept, 2018. Source: Lilium Aviation.

The Aerotropolis concept

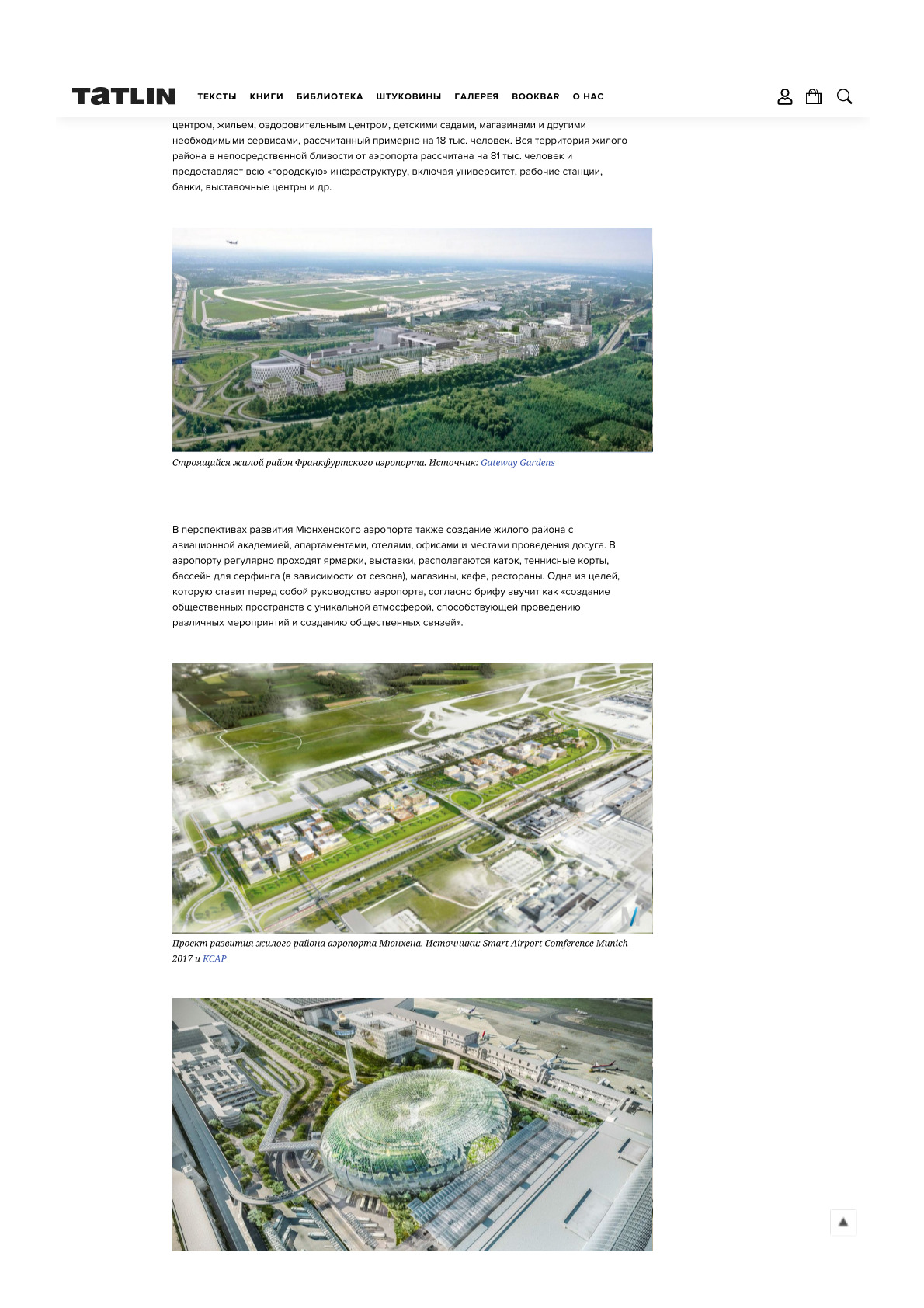

The most widely recognized model of the modern multifunctional airport is known as the Aerotropolis. The idea of an airport-centered urban form was first introduced in 1977 by McKinley Conway, founder of Site Selectionmagazine, in his book Airport City and the Future Intermodal Transportation System. However, the concept gained global prominence thanks to John D. Kasarda, a leading researcher and consultant on airport-driven development.

Since the late 1980s, Kasarda has studied and promoted the Aerotropolis model, advising major airports worldwide. In 2011, he co-authored the book Aerotropolis: The Way We’ll Live Next with journalist Greg Lindsay, describing how airports are evolving into self-sustaining urban centers that merge transport, business, and lifestyle.

Fig. 7. Aerotropolis concept by John D. Kasarda. Source: YouTube.

An Aerotropolis typically revolves around a large international hub (handling over 30 million passengers per year) focused on increasing non-aeronautical revenues through multifunctional infrastructure. This includes hotels, retail and business centers, offices, entertainment and conference venues, wellness facilities, and extensive public spaces such as parks and plazas.

Such airports are no longer just transport nodes but economic ecosystems — places where travelers, workers, residents, and local businesses interact within a unified environment. They function as regional growth engines, offering urban amenities while stimulating investment and job creation in surrounding areas.

Examples of highly developed Aerotropolises include Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (USA), Singapore Changi Airport (Singapore), Amsterdam Schiphol Airport (Netherlands), Helsinki, Vantaa Aviapolis (Finland) and many others.

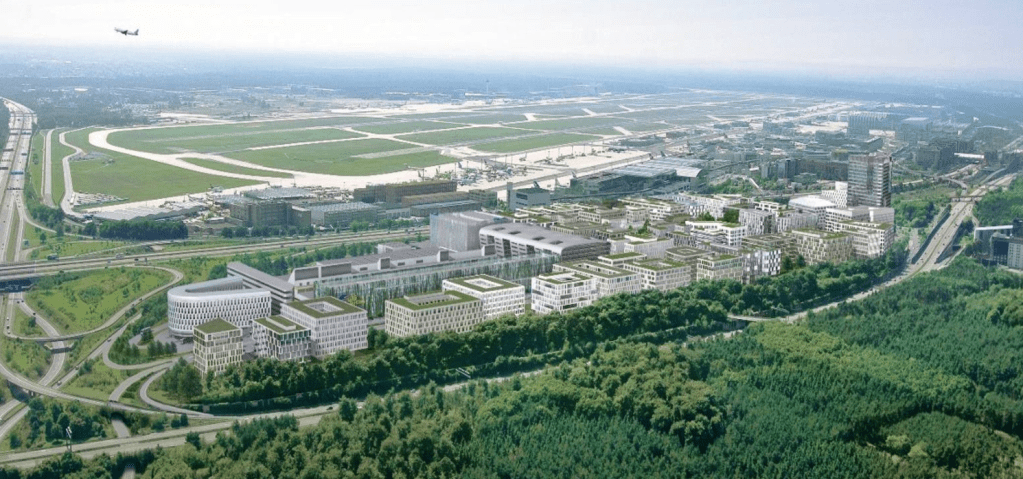

In Frankfurt, plans for “Aviacity”, part of the Gateway Gardens complex, envision a new residential and business district with housing, offices, childcare facilities, fitness centers, and retail — designed for around 18,000 residents. The wider development area near the airport is planned for over 80,000 people, with full urban infrastructure including universities, workplaces, banks, and exhibition venues.

Fig. 8. Residential district under construction at Frankfurt Airport. Source: Gateway Gardens.

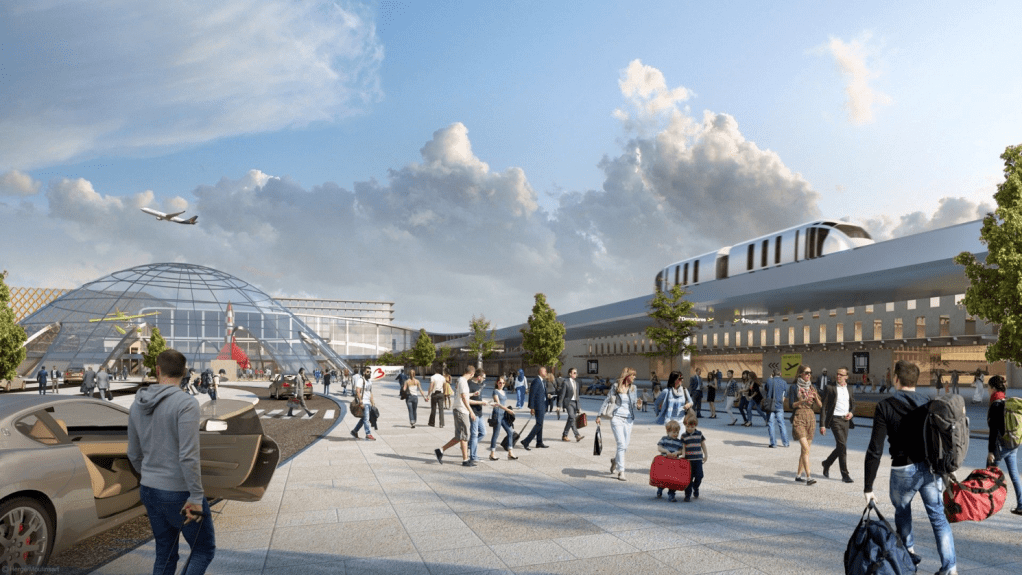

Similarly, Munich Airport’s development plans include a residential quarter with an aviation academy, apartments, hotels, and leisure facilities. The airport regularly hosts fairs and exhibitions, and its central area features a skating rink, tennis courts, and even a surfing pool depending on the season.

According to the airport’s own development brief, one of its primary goals is the creation of public spaces with a unique atmosphere — enabling events and fostering community life, transforming the airport into a true civic destination.

Fig. 9. Planned residential district at Munich Airport. Sources: Smart Airport Conference Munich 2017 and KCAP.

Fig. 10. New terminal at Singapore Changi Airport. Source: Jewel Changi.

Global trends in airport development

In total, around twenty major global trends can be identified in the evolution of modern air hubs.

Among the most significant are the steady growth of global passenger traffic and the rise of non-aeronautical revenues as key economic drivers.

Demand for air travel continues to grow in direct correlation with rising global income levels and people’s increasing need for mobility. According to World Bank data (2017), the United States remains the world’s largest aviation market, handling about 850 million passengers per year. By comparison, Russia’s passenger traffic stands at around 90 million annually, roughly equivalent to Canada, South Korea, or Australia.

Fig. 11. Screenshot from the BBC documentary series “City in the Sky.” Source: Vimeo.

The rise of non-aeronautical revenues

One of the defining trends shaping the “airport as a city” model is the rapid increase in non-aeronautical income. According to the 2014 Global Airport Economic Report, non-aeronautical revenue accounted for 40.4% of total income across the world’s 800 largest airports — nearly half of all airport earnings.

This shift has encouraged airports to evolve into multifunctional business ecosystems, attracting global corporations and developing hospitality, retail, and leisure sectors on their premises. By diversifying their income sources, airports gain greater economic stability, especially during fuel price fluctuations or global crises, when aviation demand typically declines.

Privatization and global holdings

Another major trend is the privatization and consolidation of airports under unified management groups. With market liberalization beginning in the United States, and later spreading across Europe and Russia, airport ownership and operations have increasingly moved into the private sector.

Airports are now managed as independent businesses rather than state utilities.

For example, Changi Airports International (Singapore) provides strategic management and consultancy services to over 50 airports worldwide. Meanwhile, Fraport AG (Germany) operates more than 20 airports in Europe, the United States, China, and elsewhere — including Pulkovo Airport in Russia.

Fig. 12. Billboard with Lufthansa advertising campaign at Munich Airport. Source: Smart Airports Conference Munich 2017.

The Aerotropolis model has also become a powerful branding tool. Memorable names such as Aviapolis, Aeropolis, Sky City, Aviacity, Aéroville, and AirPark are now part of the marketing strategy used to position airports as multifunctional business parks with advanced infrastructure. Global hubs actively compete for transfer passengers and corporate tenants, highlighting their commercial and lifestyle advantages.

Regional patterns and the airport as a new urban model

Other global trends include the rise of low-cost carriers, the growing importance of secondary airports, and the expansion of reserved land areas for future airport development. We also see the emergence of new urban-planning patterns such as corridor-type airport cities, the relocation of major corporate headquarters closer to airports, and the rapid integration of smart technologies into airport operations. Additionally, airports increasingly serve as public spaces, hosting exhibitions, concerts, and seasonal events — and in some cases even influencing local real-estate markets, raising property values in nearby areas.

In Russia, global aviation trends are reflected with a certain time lag. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the country’s aviation industry entered a long decline and began to recover only around the early 2000s. Even today, overall passenger traffic has not yet reached the levels of 1991. Nevertheless, Russia has also seen a wave of airport privatizations and management consolidations. For example, the “Airports of Regions” holding operates several well-known projects for new and reconstructed terminals — including Rostov-on-Don, Samara, and Saratov — managing a total of seven airports. And the Novaport Group oversees sixteen airports, while Basel Aero operates three in southern Russia.

Airport management teams increasingly recognize the importance of multifunctional development, and many projects now include plans for hotels, offices, and exhibition facilities. At Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky Airport, a new terminal, hotel, and business center are planned, while at Khabarovsk, the new terminal is expected to be complemented by an airport hotel and exhibition complex.

Fig. 13. Master plan for the development of Khabarovsk New Airport. Source: Khabarovsk Krai Investment Portal.

It would also be valuable to analyze the experience of secondary airports, which have achieved growth by hosting low-cost carriers and adopting development strategies inspired by the Aerotropolis model, despite their initially modest passenger numbers. These airports are gradually building the necessary infrastructure and attracting a variety of stakeholders at the early stages of development.

Russia’s aviation network remains highly centralized. More than 70% of all passenger traffic passes through the Moscow Air Hub (as of 2015). Outside the capital, there are still no airports exceeding 10 million passengers per year. Nevertheless, the development of regional hubs and the implementation of global best practices are now key objectives within national infrastructure programs, as aviation is recognized as a strategic driver of economic growth.

A new type of urbanism

The evolution of airports has been described — including at the Smart Airport Conference in Munich (2017) — as a “new form of urbanism.” Airports today not only support regional mobility but also integrate cities into the global economic network. Research consistently shows that improved air connectivity stimulates local business growth, while enhanced transport infrastructure contributes to GDP expansion.

The world’s largest emerging economies are currently planning the construction of around 350 new airports — in China, India, and Indonesia. Meanwhile, Turkey is building what will become the largest airport in history — a greenfield project designed to handle 250 million passengers annually, more than twice the capacity of Atlanta, the world’s busiest hub.

Fig. 14. View of the Brussels Airport cluster. Source: Smart Airport Conference Munich 2017.

The ongoing expansion of airports reflects both economic and social drivers. Their infrastructure offers vast potential for multifunctional growth. For developing countries — including Russia — the creation of an efficient air transport network can become a powerful engine of economic development, strengthening connectivity and regional governance.

As global experience shows, the world’s largest air hubs are evolving into self-sufficient urban clusters with their own economies and cultural identities. They are becoming independent centers of social and economic activity, supporting metropolitan regions while simultaneously shaping a new paradigm of 21st-century urban life.

The full text is published in TATLIN journal (in RUS).